The battles of Brentford and Turnham Green 1642 ended the King’s attempt to seize London after Edgehill. Though less well known than Edgehill, their impact was far reaching. The King never again came so close to entering his capital as a victor.

This page aims to provide historical notes to accompany God’s Vindictive Wrath by Charles Cordell. The notes are listed in order roughly matching the text. They cover the battles of Brentford and Turnham Green in 1642. This website includes more notes to earlier sections of the novel. These include the Battle of Edgehill and the Battle of Aylesbury.

Brentford in 1642

Brentford was renowned for its mud, its market, its chickens, its inns and its whores. The Great Road was poor, deep with mud and rubbish. The town had no pavement. As a staging post just outside London, Brentford had more hostelries than usual. It had 28 inns and taverns in 1793. Many were Elizabethan and older.

From Shakespeare onwards, literature tells us of Brentford’s many whores and mistresses. Famous residents included Pocahontas, Captain John Rolfe and their son Thomas.

The Three Pigeons Inn, New Brentford

‘The Three Pigeons’ was the premier inn in Brentford throughout the Elizabethan and Stuart period. Thomas Faulkner described it (1845) as a large Elizabethan building with projecting upper story. In its time, it had stabling for 100 horses. Occupying the south western corner of the Market Place, the inn ran back to the Brent. This is now the site of the London Tile Company, 194 High Street, Brentford.

English literature celebrates The Three Pigeons more than any other inn in Britain. Commonly known as ‘The Doves’, it features in Shakespeare’s The Merry Wives of Windsor (1602). It is also the scene of Decker and Middleton’s Westward Ho (1604) and The Roaring Girl or Moll Cutpurse (1611). Ben Johnson’s The Alchemist (1610) and Butler’s Hudibras (1663-78) also feature it. As does Goldsmith’s She Stoops to Conquer (1773). Finally, it appears in Dicken’s Our Mutual Friend (1865).

The Three Pigeons is also the one inn that we know Shakespeare visited with any certainty. It was also frequented by Samuel Jonson. It was a place where gentlemen entertained their mistresses. Sadly, it was demolished in 1950.

John Lowin, Joseph Taylor and the Closure of Theatres in 1642

John Lowin (1576-1659) and Joseph Taylor (158?-1652) were colleagues of Shakespeare. They were leading actors in the King’s Men theatre company at the Globe and Blackfriars theatres. Lowin was the original Falstaff. He played the part for 40 years. Taylor understudied Burbage. He was the original Hamlet and noted for his Iago. He also played a range of roles in plays by Jonson, Webster and Massinger.

Parliament closed all theatres in September 1642. Lowin seems to have taken over the Three Pigeons in Brentford at about this time. He was certainly running it, with Taylor, soon after. Neither appears to have married. Both were imprisoned for acting Rollo Duke of Normandy on 1st January 1649. Lowin died at The Three Pigeons aged 83, just before the restoration.

The “Welcome” quote appears in Hamlet, Act 2 Scene 2, enter the players. Falstaff’s “A tapster is a good trade” is from The Merry Wives of Windsor, Act 1 Scene 3. “Mistress Quickly” is from Henry IV Part 1, Henry IV Part 2, Henry V and The Merry Wives of Windsor.

Parliamentary Defences at Brentford – 10-12th November 1642

We know that Holles’ Foot manned a barricade at Brentford Bridge. It is likely that they also occupied the tower of St Lawrence’s Church. Further forward, there was an outpost at Sir Richard Wynn’s House beyond Brentford End. This occupied a site between what is now the Hilton Syon Park and the Coach and Horses on London Road. The cellars of the east wing were located in an archaeological dig by Birkbeck College in 2012.

Brooke’s Foot were stationed to the rear, in Old Brentford. It would seem that their field officers were all absent. John Lilburne arrived on the morning of 12th November and took command. As second captain, he was in theory the fifth senior officer.

Accounts vary on the number of parliamentary horse troops stationed at Brentford. Some suggest as many as seven. Either way, it would appear that they took no real part in the fighting. What is clear is that Captain Robert Vivers was captured at Brentford. Nathaniel Fiennes stated that a Robert Vivers was one of the first to run at Edgehill. This is almost certainly the same officer. He and his troop may well have been posted to Brentford to regain their honour.

The Battle of Brentford – 12th November 1642

Ludlow gives a useful account of the battle for Brentford in his Memoirs of the Life of Colonel Hutchinson. John Gwynne (Salisbury’s welsh Foot) gives another in Military Memoires of John Gwyn. John Lilburne describes the battle in, John Lilburne, Innocency and Truth Justified, 1645 (British Library E314/21).

The King’s Rendezvous on Hounslow Heath – 12th November 1642

The King assembled his army on Hounslow Heath early on the morning of 12th November 1642. ‘A True Relation of two Merchants of London who were taken prisoners by the Cavaliers and of the Misery they and the other Puritans endured’ gives a parliamentarian account of events.

“The King and Prince were then on Hounslow Heath, and were marching towards Brentford; they made full account (whatsoever is suggested to the contrary) to have surprized the City of London. Prince Robert put off his scarlet coat, which was very riche, and gave it to his man, and buckled on his armour, and put a grey coat over it, that he might not bee discovered; he talked long with the King, and often in his communication with his Majesty he scratched his head, and tore his hair as if he had been in some great discontent.

There was that day apprehended a Gentleman clothed in Scarlet, and hanged upon a tree, as it is conceived for speaking in honour of the Parliament, and no man suffered to cut him down or cover his face, until he had been made a public spectacle to the whole Army which was then marching by. This was done in the way betwixt Egham and Staines.

Dr Soame, vicar of Staines, having four or five daughters, in great jollity did ride up and down the Army, and was very familiar with the Commanders, and it was thought some of those Commanders were as familiar with his daughters; for they did ride behind some Captains, who took them up on horseback, and being more mindfull of them than of their soldiers, shewed them the whole Army, as they marched by.”

The Outpost at Sir Richard Wynn’s House – The Prince of Wales Horse and Forlorn Hope

Edward Ludlow tells us that the King advanced. “Taking advantage of a very thick mist marched his army within half a mile of Brentford before he was discovered.” The advance was led by The Prince of Wales’ Regiment of Horse. They were part of Rupert’s brigade of horse, on the King’s right.

In the fog, the Prince of Wales Horse ran into Holle’s outpost at Wynn’s House. Here they were met by cannon fire. “They played so fast upon us, that we lost some Men, and were obliged to draw off”. Lieutenant Thomas Daniell was killed and William Tirwhitt lost an arm.

The King’s Forlorn Hope now fell on the outpost. This consisted of an advanced guard of 1,000 musketeers. A single foot company probably manned the outpost as Grand Guard. It is unlikely that they withstood the storm of fire for long.

The Barricade at Brentford Bridge – Holle’s Foot and Salisbury’s Welsh

Salisbury’s Welsh Foot appear to have been the lead battalion of the King’s vanguard. Sir Thomas Salisbury addressed his regiment with the words, “gentlemen, you lost your honour at Edgehill. I hope you will regain it here.” It must have stung their pride. They went on to storm Holle’s barricade at Brentford Bridge.

John Gwynne gives an account of the battle for Brentford in his Military Memoires of John Gwyn. He joined the regiment on Hounslow Heath and went on to lead one of its companies.

“We had no sooner put ourselves into rank and file, under the command of our worthy old acquaintance, Sir George Bunckley, (then Major to Sir Thomas Salisbury) but we marched up to the enemy, engaged them by Sir Richard Winn’s house, and the Thames side, beat them to retreat into Brentford, – beat them from one Brentford to the other, and from thence to the open field, with resolute and expeditious fighting, that after once firing suddenly to advance up to push of pikes and butt-end of muskets, which proved so fatal to Holles his butchers and dyers that day, that abundance of them were killed and taken prisoners.”

John Lilburne’s Barricade – Lord Brooke’s Regiment of Foot

With Brentford Bridge cleared, the fighting rolled up Brentford High Street. A second barricade, manned by Brooke’s Foot, halted the royalist advance. John Lilburne commanded here. His speech is taken from his own account of the battle.

The position of this second barricade is not certain. However, the junction of the High Street with Drum Lane (now the B455 Ealing Road) would seem to fit. It has the advantage of slope, firm flank against the Thames and a clear field of fire. It also fits the description of being “between the two Brentfords”. The proximity of Lot Ait and Brentford Ait islands also fit well.

The Red Lion Inn occupied the corner of Drum Lane and Brentford High Street until demolished in 1962. The 1841 tithe map marks it with a substantial courtyard. Henry VI held a chapter of the Order of the Garter at the Lion Inn, Brentford in 1445. The site is now occupied by Osier Court.

The King’s Foot Assault – Wentworth’s Tertia and Fitton’s Cheshire’s

Wentworth’s Tertia formed the royalist vanguard. This included: Salisbury’s (Welsh), G Gerard’s (Lancashire), Molineaux’s (Lancashire), Belasyse’s (Yorks & Notts) and Blagge’s (Suffolk) foot regiments. Mathew Smallwood describes five regiments assaulting Brooke’s barricade. Each one was beaten back. Finally, Fitton’s (Cheshire) regiment broke through with the aid of two cannon “newly brought up”. The five failed assaults were almost certainly those of Wentworth’s Tertia.

Fitton’s were probably the lead foot regiment of Fielding’s Tertia that made up the main body, or Battle, that day. Lunsford’s and River’s foot regiments also fought at Brentford. They may have been the two regiments that went on to clash with Hampden’s green-coats advancing towards Brentford from Acton. The other regiments of Fielding’s Tertia were probably: Fielding’s, Bolle’s, Stradling’s and Northampton’s foot.

Byron’s Tertia probably made up the royalist Rear for that day. It seems that it was not engaged. It is likely that the Lifeguard of Foot would have been with the King at Boston Manor overnight after Brentford. The other foot regiments of this tertia were probably: the Lord General’s, Beaumont’s, C Gerard’s, Dutton’s and Dyve’s.

Pennyman’s Foot was probably also part of Wentworth’s Tertia. However, there is no mention of it at Brentford. It is possible that it remained behind to screen Venn’s parliamentary garrison at Windsor.

Encirclement – Boston Manor, Osterley – Wilmot’s Brigade of Horse

It is likely that some of the King’s horse worked around to the north. Defoe’s Memoirs of a Cavalier, written within living memory, describe such a move. “At last, seeing the obstinacy of these men, a party of horse was ordered to round from Osterley; and, entering the town on the north side.”

If such a move took place, it is likely that Wilmot’s brigade of horse would have completed it. This included Grandison’s Horse. Walsingham’s Account of the Doings of Sir John Smith describes Smith’s “gallant behaviour in the fight at Brainceford [Brentford]”.

The route taken was likely to have followed the route of the modern Great West Road (A4). The crossing point over the River Brent was probably near Boston Manor. Such a flank move would have entered Brentford down Half Acre or Drum Lane.

Defenders Shot and Drowned in the Thames

A number of accounts state that defenders tried to escape by swimming across the Thames. They are clear that many drowned. Mathew Smallwood (Fitton’s) gives a clear account from a royalist perspective.

“What was most pitiful was to see how many poor men ended and lost their lives striving to save them, for they ran into the Thames, about 200 of them, as we might judge, were drowned.”

It was possible to ford the Thames at Brentford, before it was dredged. (Julius Caesar probably crossed the Thames here in 54 BC.) However, this was only possible at low tide. The 12th November 1642 was a new moon and would have seen spring tides with high rise, fall and flow of water.

A number of parliamentary accounts suggest that mounted cavaliers rode along the banks of the Thames shooting at some of those in the water. This may be propaganda. But it is equally possible that undisciplined troops ran amok.

The Sack of Brentford

The King’s opponents expressed outrage at Royalist actions at Brentford. They saw the attack as a “bloody and treacherous design”. See Special Passages, anon, Nov 1642. Some compared the sack of Brentford to the worst atrocities of the Thirty Years War. It did no compare. But, it did scare the citizens of London.

Many accused Salisbury’s Welsh Foot of plundering. They had a bad reputation throughout the war. Even Royalist officers complained of the thieving ways of the Welsh foot. (See Thomason Tract E.128 (34).) They appeared to be ignorant of political differences, robbing parliamentarian and royalist alike. Equally, these accusations probably reflected racist views at the time.

Prisoners taken at Brentford were bound head to toe and kept in the cattle Pound. This was an enclosure for animals impounded for illegal grazing. The Pound was almost certainly adjacent to Brentford’s Lock-Up House, or parish jail. The1839 tithe map marks the Lock-Up at the junction of Ferry Lane and Brentford High Street. Brentford Fire Station replaced it in 1897. Today it is a café.

Barges on the Thames – 13th November 1642

Early next morning, a number of barges attempted to pass Brentford. They were carrying 2,000 reinforcements and munitions to Essex in London. Colonel Blagge was stationed at Syon House with two cannons. He engaged and sank a number of these barges.

John Gwyn describes the explosion of a powder barge. “And at that very time were come a great recruit [reinforcement] of men to the enemy, both by land and water, from Windsor and Kingston.”

Essex’s Army was at Kingston, Acton and Chiswick, with the artillery at Knightsbridge. Ludlow was with Essex’s Lifeguard of Horse at Chelsea Fields. The noise of the explosion reached him downriver.

The Battle of Turnham Green – 13th November 1642

News of the royalist attack at Brentford provoked a swift response. Despite the tactical victory, the chance of strategic success was lost. The London trained bands came pouring out of the city to join Essex.

By 0800 in the morning, 20,000 parliamentary horse and foot were in place. They ranged across Acton Common, Turnham Green and Chiswick Common Field. Sergeant Major Phillip Skippon encouraged the London foot with his immortal words.

“Come my boys, my brave boys, let us pray heartily and fight heartily, I will run the same fortunes and hazards with you. Remember the cause is God, and for the defence of your selves, your wives and children. Come my honest brave boys pray heartily and God will bless us.”

Parliamentary accounts state that Rupert made several charges and “did lay about him like a fury”. He was shot at “a thousand times”, but not touched. However, the King was outnumbered and short of ammunition. John Gwyn later explained,

“Nor can anything of a soldier or an impartial man say, that we might have advanced any further to the purpose of towards London than we did … and withal considering that they were more than double our number; therefor the King withdrew.”

Prince Rupert ordered 500 muskets onto Brentford Bridge. When the Prince arrived at the Bridge, he found Sir Jacob Astley almost alone. Rupert sat on his horse in the river until the King’s army was across the Brent.

The King’s withdrawal in good order dissuaded Essex from pursuing. However, the opportunity to seize London had gone. The war would not be over by Christmas.

War Widows, Petitions and Pensions – Thomasine Bennett

Parliament awarded some 80 pensions to war widows for their husbands’ defence of Brentford. Thomasine Bennett was one of those. In 1654 she petitioned Cromwell to reinstate the pension for her and her eight children. She cited Captain William Bennett as “the chief instrument” of holding back the royalist attack.

If interested, there is now a fanatic source for the study of Civil War Petitions. This project looks at welfare and memory during and after the British Civil Wars, 1642-1710.

More Reading

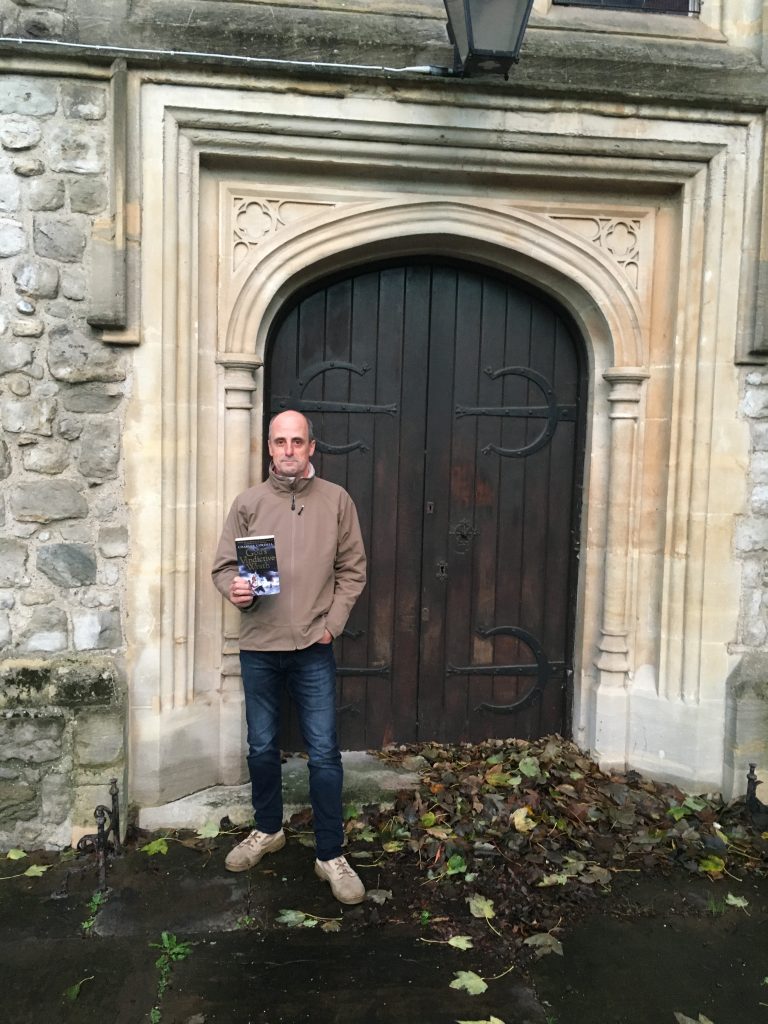

I hope you found these notes on the battles of Brentford and Turnham Green in 1642 useful. I hope you will enjoy reading the story of these battles in God’s Vindictive Wrath, book one of the Divided Kingdom series of English Civil War historical fiction. It is as close to the historical events as I can make it.

You may also want to read my notes on the Battle of Edgehill. This site also has notes on the Battle of Aylesbury, the peace talks at Colnbrook and London’s Lines of Communication.

You can also read about Pike and Shot Warfare. This article explains the clash between Dutch and Swedish military doctrines at Edgehill in 1642. More articles on The General Crisis of the 17th Century, including the Wars of Religion and The Thirty Years War, and the Great Rebellion of 1642 are also at Notes and Maps.

If you want more, you can join the Divided Kingdom Readers’ Club. You will receive a monthly email from me including more notes from my research. If you think this is for you, please do join the Clubmen.

Alternatively, return to the site Home Page for information about Charles Cordell, latest posts and links to books.