The Storming of Winchester in 1642 was an extraordinary moment in the English Civil War. It marked the close of the first campaign season and year of the war, in December 1642, with a victory for Parliament. But, it came with a shocking level of iconoclastic fury.

Its result was effectively to open a corridor for Parliament from London to Bristol and to separate the King in Oxford from support in Cornwall. However, the storming of Winchester was itself marked by a new level of religious fanaticism in the desecration of Winchester Cathedral and its close.

This page aims to provide historical notes to accompany Desecration, a short story by Charles Cordell. The notes are listed in order roughly matching the text. They cover the Storming of Winchester in 1642. This website also includes notes to accompany the text of the novel God’s Vindictive Wrath, including the battles of Edgehill and Brentford, as well as articles on the General Crisis of the 17th Century and the causes of conflict in the British Civil Wars.

Winchester in 1642

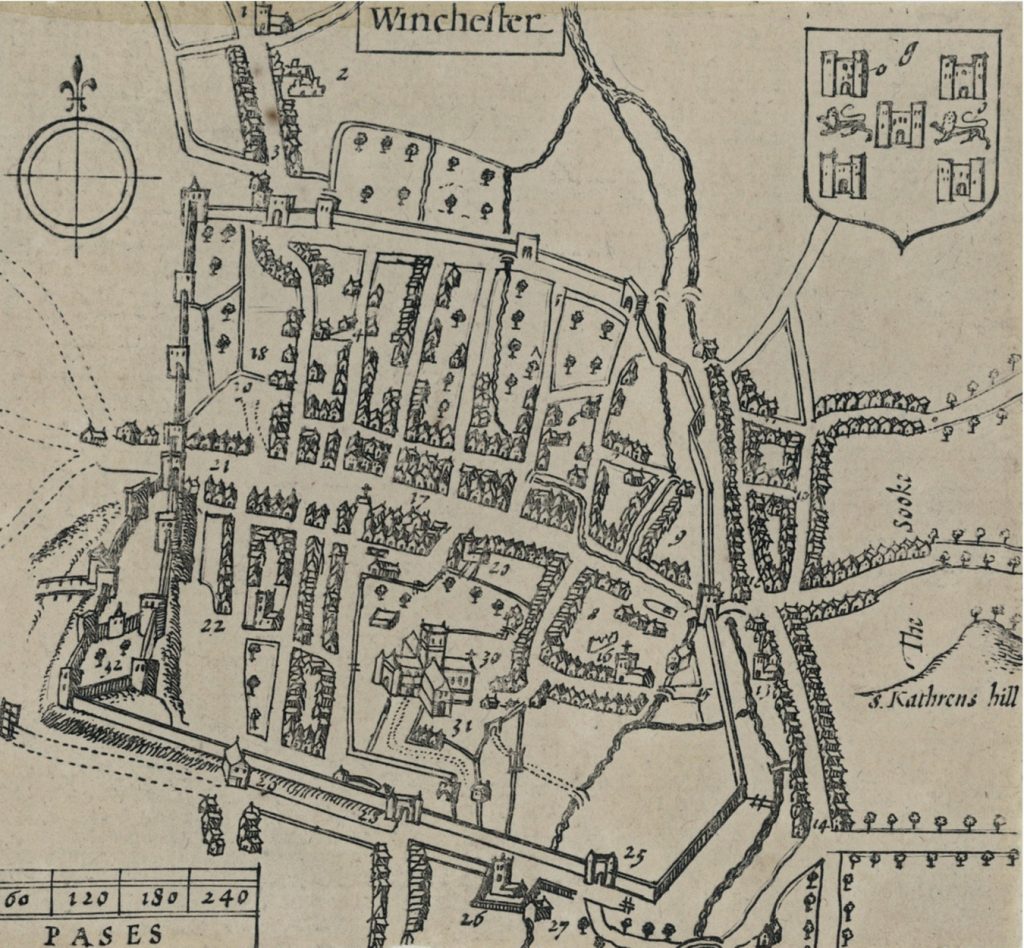

Winchester was and is the county town of Hampshire in southern England. It was key to communications between London and the ports of Portsmouth, Gosport and Southampton. Perhaps more importantly, it was the ancient capital of Wessex and the burial place of many of the early kings, queens and bishops of England.

The city was dominated by its cathedral and castle. Built in 1079, the cathedral remains the longest Gothic cathedral in Europe. A site of medieval pilgrimage, it was still richly decorated in 1642. Little remains of Winchester Castle, other than its Great Hall and subterranean passages. However, in 1642, it still stood as a significant fortification. Much of the castle was later replaced by the King’s House, an attempt by Charles II to build a ‘Versailles’ in England.

Winchester remained, in 1642, largely within its Roman and medieval city walls. However, these walls were in a poor state in many places. Critically, Winchester Castle and town were ill-prepared for a siege. Little food or powder was stockpiled and no cannon had been procured.

The King’s Forces in Winchester

Lord Grandison commanded the King’s forces in Winchester in December 1642. He had with him his regiment of horse and Grey’s Dragoons. Both regiments had played active roles at the Battle of Edgehill and the Storming of Marlborough on the 5th of December. However, by December, Grandison’s Horse was probably only about three hundred strong and Grey’s Dragoons no more than two hundred.

The seizing of Marlborough gave the King an important post on the Great Road from Bristol to London. One thousand prisoners, four colours, four cannon, arms, powder, match and shot were taken. All were marched to Oxford with Lord Wilmot. However, the fire that swept through Marlborough’s market place after the fighting destroyed much needed supplies. In particular, it consumed a quantity of woollen cloth needed to cloth the King’s army for winter.

From Marlborough, Grandison attempted to relieve Basing House, via Newbury and Andover. This had resulted in a clash with a force under Sir William Waller that had successfully taken Portsmouth and Farnham for Parliament. Pursued by Waller, Grandison made for Winchester where he assumed command of the local militia regiment of trained bands.

The Parliamentary Forces in the South

Sir William Waller had with him four regiments of horse and two of dragoons. These would appear to have included Balfour’s Regiment of Horse, with Lieutenant Colonel Urrey and Captain Nathaniel Fiennes both reported as being present. We also know that Colonel Balfour was responsible for Lord Grandison’s parole, following his surrender.

Waller’s force also included Browne’s Regiment of Dragoons. He caught up with Grandison outside Winchester on Monday 12th December 1642. However, his force included no cannon and no foot. He was, therefore, ill-prepared to conduct a siege.

The Storming of Winchester – 12th December 1642

Initially, Lord Grandison faced Waller on the open country to the west of Winchester. Some reports suggest he marched out with a mixed force of horse and foot. However, he was driven back to the city walls, with the loss of a number taken prisoner or killed.

Captain Sir John Smith, Major Sir Richard Willis and eighteen men made a stand outside the walls. This was almost certainly a rear-guard action to cover the retreat of the rest of Grandison’s Horse into Winchester. They were charged three times before finally following Grandison inside the city. Almost certainly, they made their retreat through the West Gate, which still stands today.

Waller reported ‘we cut off two regiments, one of horse, and another of dragooneers, 600 of whom were gallant horse. We began our fight five miles wide of Winchester towards Salisbury way.’

Waller launched his assault on the walls of Winchester at noon on the 12th of December. At some point between 14:00 and 15:00, led by their sergeant-major, Brown’s Dragoons succeeded in breaching the walls. This is recorded as being in a place where the city walls were broken down. The defence mounted by the city militia quickly collapsed.

Grandison retreated into the Castle. This was probably shortly before or around sunset, which would have occurred at 15:58. In the ensuing darkness, Waller’s troopers piled timber and tar against the castle gate ready to burn it down. Sir John Smith proposed a sally, but Grandison is reported as deciding against it. At about 22:00-23:00 he requested a parley.

The Surrender of Winchester Castle

A parley was granted at daybreak on Tuesday 13th December and agreed terms of surrender. These conclude that the King’s officers were to be taken as prisoners to Portsmouth, then Lambeth House in London. All arms, horses and money were to be surrendered. The rank and file were to be set free, on foot.

However, contrary to the terms of surrender, many of the King’s troopers and dragoons were ill-treated. Some were stripped of items of clothing and their personal purses robbed. A letter from Edward Walker to the Earl of Lindsay, dated 21st December 1642, describes the scene.

‘But conditions were not kept they say, the rude multitude overswaying their officers, so that our officers being detained were enforced to make escapes, as the Lord Grandison, Sir Richard Willis and some few others, but as yet your Lordship’s brother [Lord John Stuart] and Sir John Smith are not come to us and, as I hear, but ill treated.’

I can find no clear evidence for where this happened. However, the Cathedral Close would seem a likely location. Waller would almost certainly wish to separate the Royalist troopers from their officers as quickly as possible. He would also want to get them out of the castle and into an enclosed space where their horses could be held. The cathedral Close fits this well.

Lord Grandison and Other Prisoners

The prisoners were: Col Lord Grandison, Maj Sir Richrad Willis, Sir John Smith, Major Hayborne; captains Garret, Honeywood, Barty, Booth, Brangling, Wren, Beckonhear; lieutenants Williamson, Rogers, Elverton, Rodham, Booth; cornets Bennett, Savage, Ruddry, Gwynn and Bradlines. Local county gentlemen prisoners included: Sir John Mills of Mottisfont, Sir Thomas Phillips of Stoke Charity, his brother Sir Francis Powre, Master Powlet and his son.

Grandison, Major Willis and one or two other officers escaped on road to Portsmouth. Urrey was suspected and accused of conniving but later acquitted. Later, Sir William Balfour (at Windsor) sent a trumpeter with a message to Grandison (at Oxford) accusing him of breaking his parole as Balfour’s prisoner. Grandison, with Rupert’s support, sent a response which arrived at Windsor on 17th January 1643 offering to meet Balfour in a duel.

The Sacking of the Cathedral Close

Many of the houses within the Cathedral Close were sacked. This probably occurred during the storming of the city. One of Waller’s own soldiers described the situation.

‘Our soldiers most notably plundered and pillaged their houses, taking whatsoever they liked best out of them, but chiefly some Papists’ houses there, and the sweet Cathedralists, in whose houses and studies they found great store of Popish books, pictures, and crucifixes, which the soldiers carried up and down the streets and market-place in triumph to make themselves merry.’

The Cleansing of Winchester Cathedral

At some point, Waller’s troopers broke open the cathedral doors and defaced much of the interior. GN Goodwin, in his The Civil War in Hampshire, describes this as being on the morning of the 14th of December. However, his days of the week do not tally with his dates. It would seem much more probable that this occurred earlier, at some point on Tuesday 13th, before Waller could restore order amongst his victorious troopers and dragoons.

Mercurious Rusticus describes the scene from a Royalist point of view. ‘The doors being open as if they meant to invade God himself, as well as His profession, they enter the church with colours flying, their drums beating, their matches fired, and that all might have their part in so horrid an attempt, some of their troops of horse also accompanied them in their march, and rode up through the body of the church and quire, until they came to the altar;

‘there they begin their work, they rudely plucked down the table, and break the rail, and afterwards carrying it to an ale-house, they set it on fire, and in that fire burnt the books of Common Prayer, and all the singing books belonging to the quire; they throw down the organ, and break the stones of the Old and New Testament, curiously cut out in carved work, beautified with colours, and set round about the top of the stalls of the quire;‘

The Desecration of the Saxon King’s and Bishops

Perhaps the most extraordinary act was the scattering of the bones of the Saxon kings and bishops. These relics reposed in individual mortuary boxes in the cathedral chancel. To this day, nobody is sure which bones are now in which mortuary box. Some of the bones were used to smash the stained glass. Mercurius Rusticus continues,

‘From hence they turn to the monuments of the dead, some they utterly demolish, others they deface. They begin with Bishop Fox his chapel, which they utterly deface, they break all the glass windows of this chapel, not because they had any pictures in them, either of Patriarch, Prophet, Apostle, or Saint, but because they were of painted coloured glass; they demolished and overturned the monuments of Cardinal Beaufort, son to John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, by Katharine Swynford, founder of the hospital of St Cross, near Winchester, who sat Bishop of this See forty-three years.

‘They deface the monument of William of Wainfleet, Bishop likewise of Winchester, Lord Chancellor of England, and the magnificent founder of Magdalen College in Oxford, which monument in a grateful piety, being lately beautified by some that have or lately have had, relation to that foundation, made these rebels more eager upon it, to deface it, but while that college, the unparalleled example of his bounty, stands in despite of the malice of these inhuman rebels, William of Wainfleet cannot want a more lasting monument to transmit his memory to posterity. From hence they go into Queen Marie’s chapel, so called because in it she was married to King Philip of Spain; here they break the Communion table in pieces, and the velvet chair.’

Radical Religious Thinking in the 1640s

These actions may appear to be random acts of vandalism. However, they should be understood in the context of radical religious thinking prevalent amongst many who fought for Parliament. It must also be remembered that, on 8thSeptember 1641, the House of Commons had ordered the cleansing of English churches.

Every parish was to ‘forthwith remove the Communion Table from the east-end of the church, chapel, or chancel, into some other convenient place.’ This included the removal of altar rails and levelling of chancel steps.

Crucifixes, pictures of any person of the Holy Trinity, and images of the Virgin were to be removed and destroyed. All tapers, candlesticks, and basons were to be removed from the Communion Table. ‘All corporal bowing at the name [of Jesus] or towards the east-end of any church, chapel, or chancel be henceforth forborne.’

The Destruction of Human Images & Hymn Books

Some radicals interpreted these new laws as banning any human image from churches. They were seen as profane, in line with Deuteronomy 4:16, ‘Lest ye corrupt yourselves, and make you a graven image, the similitude of any figure, the likeness of male or female.’ As a result, many human images in stained glass, as well as statues, were smashed.

Finally, it is worth understanding radical thinking on the singing of hymns. Much of this was based on Calvinist thinking. This promoted the singing of Psalms as the words of God set down in the Bible. However, the words of man were not fit to be heard in the house of God. This included the banning of tradition medieval Gregorian chants and Elizabethan choral arias. Zwingli went further in rejecting all music in worship. Hymn books and organs were, therefore, cast out.

Other Winchester Civil War Stories

One Winchester site that was not apparently subjected to sacking was Winchester College. It is reported that Captain Nathaniel Fiennes, of Balfour’s Horse, placed a guard to protect the school from the marauding troops. He was himself an old Wykehamist schoolboy. He was shortly to go on to raise his own regiment of horse and install himself as the parliamentary governor of Bristol. But that is another story – the story told in The Keys of Hell and Death.

Finally, a local tradition states that the site of Barclays Bank on Jewry Street is haunted by a Royalist tortured during the Civil War. It was the site of a 17th-century stable block. One Master Say tried to save his horses from pillage and was betrayed by his servant. He was hauled up by a bridle placed around his neck and almost-but-not-quite strangled. Rasping and choking sounds used to be heard, when the building was a hotel, followed by the thud of a body falling onto the cobbled floor. On a recent visit to Winchester, I talked to a lady who told me that it is still an eerie place.

More Reading

I hope you found these notes on the Storming of Winchester in 1642 useful. You may also want to read my notes on the Battle of Edgehill. This site also has notes on the Battle of Aylesbury, the peace talks at Colnbrook, London’s Lines of Communication and the Battles of Brentford and Turnham Green.

You can also read about Pike and Shot Warfare. This article explains the clash between Dutch and Swedish military doctrines at Edgehill in 1642. More articles on The General Crisis, including the Wars of Religion and The Thirty Years War, and the English Revolution and Great Rebellion are also at Notes and Maps.

If you want more, you can join the Divided Kingdom Readers’ Club. You will receive a monthly email from me including more notes from my research. If you think this is for you, please do join the Clubmen.

Alternatively, return to the site Home Page for information about Charles Cordell, latest posts and links to books.