The Edgehill to London 1642 campaign followed the Battle of Edgehill. Had it succeeded, it would have ended the English Civil War within three months. Its failure led to the protracted slaughter of the British Civil Wars – the bloodiest period in British history.

This page aims to provide historical notes to accompany God’s Vindictive Wrath by Charles Cordell. The notes are listed in order roughly matching the text. They cover the campaign from Edgehill to London in 1642. This website includes more notes that may be of interest. These include the Battle of Edgehill and the Battle of Brentford.

Essex’s Withdrawal – Kineton to Warwick – 24-25th October 1642

On the morning on of 24th October, Essex’s army drew out of Kineton and formed up again. They remained in place for 3 to 4 hours before returning to Kineton. Edmund Ludlow recounted, “about daylight we saw the enemy upon the top of the hill: so that we had time to bury our dead; and theirs too if we thought fit. That day was spent in sending trumpeters to enquire whether such as were missing on both sides were killed or prisoner.”

Essex left his army on the afternoon of 24th and withdrew to Warwick Castle. It is not clear why he did this. He may have felt an obligation to personally care for the wounded Earl of Lindsey. The King’s Field Marshal died in Essex’s coach before they reached Warwick.

On the morning of 25th, Rupert entered Kineton. He found that most of Essex’s army had also left for Warwick. However, he captured 25 wagons and carriages laden with ammunition, medicaments and other baggage. “He brought away part and fired the rest”. Sick and wounded apparently lay in every house in Kineton. This was probably the tail end of Essex’s army. A thick mist hindered any further pursuit.

The King’s Quarters – Culworth, Chipping Warden, Aston le Walls – 24-26th October 1642

We know the King’s army had marched from Southam on 22nd October in three brigades. These were probably under Sir Nicholas Byron (Van for that day), Richard Fielding (Centre) and Charles Gerard (Rear). We know that Lord Lindsey quartered at Culworth Hall with the Van on the night of 22nd October.

Almost certainly the other brigades quartered along the line of march, at Chipping Warden, Aston le Walls and possibly the Boddingtons. We know that the King had settled for the night at Sir William Chauncie’s house at Edgcote. The Artillery Train was at Wardington on 25th October 1642. It may well have been there earlier in readiness for the planned assault on Banbury.

Rupert had stayed at Lord Spencer’s House at Wormleighton. At least on regiment of horse, the Prince of Wales’, was at Warmington. It is likely that his brigade (four horse and one dragoon regiments) quartered in an arc covering the rear of the King’s army. Regiments were probably centred on Wormleighton, Fenny Compton, Avon Dassett, Warmington and Ratley. Finally, we know that troops also quartered at Cropredy.

Almost certainly, Wilmot’s brigade (five horse and two dragoon regiments) took positions in an arc covering the line of advance and Banbury. Probable quarters include Eydon, where at least one royalist casualty of the battle was buried. They also include Weston, Sulgrave, Thorpe Mandeville, Chacombe, Williamscot, Cropredy and perhaps the Bourtons.

The King’s Rendezvous – Edgcote – 26th October 1642

The King reviewed his army at Edgcote on 26th October 1642. It became clear at this rendezvous that his army was ready to march. His Welsh regiments in particular benefitted from the arms captured at Kineton.

Edward Walsingham gives an account of Sir John Smith’s exploits, in his Brittannicae Virtutis Imago, Oxford 1644. He makes clear that the King granted Smith command of a troop of horse. “These valiant actions made him very eminent in His Majesties sight, so that the royall munificence gives him a troope of his owne.”

It would seem likely that this promotion took place at the Edgcote rendezvous, in front of the army. Grandison’s Horse included a Lieutenant Rogers. He was among the officers captured at Winchester.

The wording of Smith’s commission is taken from that granted to Captain Roger Whitley on the 1st of November 1642. A British Army officer’s commission today remains remarkably unchanged. The wording of the King’s laws and ordinances is from Military Orders, and Articles established by His Majestie, for the Better Ordering and Government of his Majesties Armie.

Little Bourton

Both Great and Little Bourton were hamlets within the parish of Cropredy. They were relatively poor communities in the 17th Century. In 1665, only 30 people were taxed between the them. Just three houses containing more than 2 hearths, the vast majority having only one. Cottages were of ironstone and thatch. Few owned animals. Farming was mostly wheat, barley and peas. Great Bourton Chapel was desecrated during the Reformation and not rebuilt until 1863. The ‘Bell’ inn was thatched until a fire in the 1920s.

Little Bourton was later described as giving Waller “very great advantage” ahead of the battle of Cropredy Bridge (1644). It was almost certainly occupied as a Royalist outpost facing Banbury. Much of Old Manor Farm is 17thCentury. It is likely to be the original Little Bourton Manor, owned by Josiah Gardner in 1642.

Surrender of Banbury – 27th October 1642

Banbury was a town with Puritan sympathies. A common cry was “Banbury zealots, cakes and ale”. However, the castle garrison and town surrendered to the King without a fight on the 27th of October.

Banbury was renowned in the 17th Century for fine cheese, ale and cakes. Gervase Markham includes a recipe for Banbury cake in his celebrated ‘The English Housewife’ of 1615. We know that Betty White sold Banbury cakes from a shop in Parson’s Street in 1638. Her husband, Jarvis White, had a habit of hanging over the door of his shop to talk to those in the street, rather than working within the shop.

Despite their sympathies, it would seem likely that some traders were open to the King’s army. The King’s summons almost certainly interrupted the usual Thursday market.

The ancient drovers’ way to London followed a path south of Banbury and Crouch Hill. It passed through Bodicote and Aynho. The King’s move to Aynho put him in a position with options. He could now move south to Oxford, or south east, directly to London. It is this move that allowed the King to claim a victory. It put fear into those who opposed him, particularly in London.

The King’s March – Aynho, Deddington – 28th October 1642

The next day, Rupert seized Broughton, the home of the rebel Lord Saye. Rupert proposed a dash for London with a flying column of horse. He was countermanded. But the way was now open for the King to move south towards Oxford.

Slat Mill sits below Little Bourton on the Cherwell River. The ford was to play a vital role in the battle of Cropredy Bridge in 1644. Before the Oxford Canal was dug, the Cherwell was much wider.

Deddington sits on the road from Banbury to Oxford. Now the A4260, this road runs parallel with the Cherwell River. However, Deddington was impoverished following enclosure. The church tower collapsed in 1634. The castle was in ruins by the 14th Century. A local rhyme tells, “Aynho on the hill; Clifton in the clay; Dirty, drunken, Deddington; and Hempton highway.”

The Market Place lies to the east of the modern High Street. In 1855 it was still an “ugly piece of rocky ground”. It contained a market cross and a town pond regularly polluted with offal from the market. It also included at least two rows of “decayed” shops. The Unicorn Inn has a 19th Century front, but 17th Century features remain. It included its own malthouse for brewing ale. Indeed, the town had a reputation for its “malt liquor”.

Islip and Woodstock

Islip lies on what was the highway from Wales and Worcester to London. Its bridge across the Ray made it a place of strategic importance during the Civil War. As did its proximity to the Cherwell. It changed hands a number of times during the war. This included a skirmish, between Cromwell and Northampton in 1645, on Islip Bridge itself.

The town had at least eight inns, of which only three survive. The ‘Prince’s Arms’ was across the street from the ‘Red Lion’. It was reputed to have been built using the remains of Edward the Confessor’s chapel. It was the hostelry for gentry. Sadly, nothing appears to remain today. The ‘Red Lion’ was the tap-house for carters.

We know that the King halted at his palace at Woodstock for the night of 28th October 1642. This probably allowed the rearguard to catch up before entering Oxford the next day. The roads must have been in terrible condition in the Autumn rains.

Conditions of the 17th Century Poor – Oddington in 1642

Oddington had not been a prosperous village from the ‘Doomsday’ record forward. The village lies on the edge of Otmoor in a near flat, treeless landscape. The clay land is heavy and yielded a poor return. The cottagers of the village depended heavily on pasture grazing and common rights for survival.

In 1662, the village consisted of sixteen households. Of these, only one was a farmhouse of more than one or two hearths. The manor was deeply indebted during the 17th Century. It apparently spent long periods unoccupied. It was finally pulled down in the 18th Century. The rectory kitchen and barn had collapsed by 1676 and the building taxed on only one hearth.

The accommodation of animals and humans under a single roof persisted well into this era. This was despite advances in building techniques. William Harrison noted them in the fen counties and North of England. In some areas, they persisted into the 19th Century. Howitt’s Rural Life in England describes a similar cottage and scene of rural poverty as late as 1840.

Bread was an essential part of almost every meal in early modern England. It was vital in providing basic nutrition and bulk, for the majority of the population, throughout the year. Most poor cottagers and peasants lacked access to an oven. They baked their bread on a flat stone known as a bakestone. This was a method used from prehistory until at least the early 20th Century. Dependent upon local growing conditions, different meal mixes were used. These could be wheat with barley or rye, barley with pea, or rye with pea. The term for this mixed flour is ‘drage’.

Housework, Night Rituals and Sleep in Pre-Industrial Britain

It was common for medieval English women to spend protracted periods squatting on their haunches. We know this from skeletal remains. Today, we think of this as an Asian or African practice. However, it was almost certainly the normal position adopted in early modern England. Poorer cottages would have contained very few items of furniture. Almost all food preparation would have been conducted at floor-level.

The rituals described before bed would have been common in most households in 17th Century England. Evening devotions were habitual. They would have been led by the head of the household. He would administer to any servants as well as his family. Spiritual protection, as well as physical, was considered a very real necessity. However, in many rural areas the form taken was often more akin to a charm or night-spell than conventional prayer.

The normal pattern of sleep in pre-industrial Britain was broken. It included a period of waking in the middle of the night. We know this from a good deal of literary evidence. Most people would wake at 0100-0200, between their “first sleep” and “second sleep”. It was not unusual for servants and labourers to get up to perform chores. Howitt describes a boy getting up in the night to protect crops from deer, in his Rural Life in England. This pattern of sleep is still normal in parts of Africa. For more, see Roger Ekirch, Sleep We Have Lost: Pre-Industrial Slumber in the British Isles.

Oxford – 29th to 30th October 1642

The King and his “whole army” entered Oxford on Saturday 29 October 1642. The King was greeted with the words “our Oxford hath thrown off all clouds of discontent, stands clear, gilded by the beams of Your Majesty’s royal presence”. He quartered in Christchurch. The artillery parked in Magdalen Grove.

Christopher Merritt (1615-95) studied at Oriel College. This English physician and scientist created the glass bottle strong enough to contain champagne. Without him, there would be no fizz.

Robert Evans reported the arrival of the King’s army as follows: “The King intends for London with all speed. Reading must be inhumanly plundered. One Blake, or Blakewell, I know not whether, was this day hanged, drawn and quartered, in Oxon, for receiving 50l. a week from Parliament for intelligence, he being privy chamberlain to Prince Robert. We were in Oxon streets under pole axes, the Cavaliers so out-braved it. The King’s horse there, with seven thousand dragoons. The foot I know not, save that Colonel Salisbury (my countryman) hath twelve hundred poor Welsh vermin, the offscouring of that nation.”

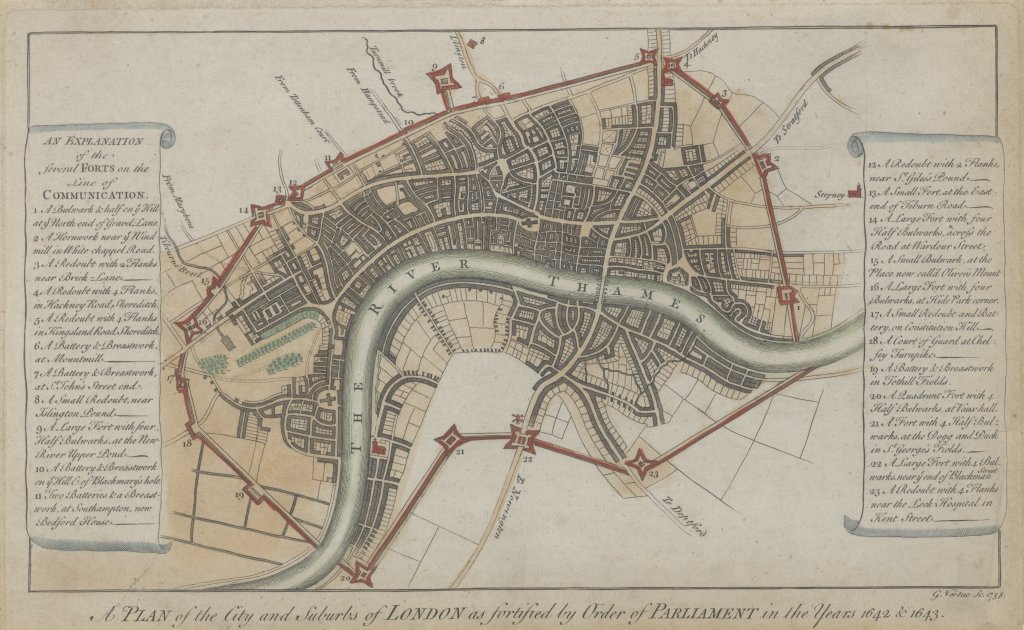

London’s Defences – The Lines of Communication

London began to prepare defences almost as soon as hostilities commenced. However, these became a much more serious undertaking after Edgehill. There was a real sense of their need.

As many as 20,000 people a day laboured on the London defences. Women and children joined worked alongside men. Samuel Butler’s ‘Hudibras’ includes the famous lines, “From Ladies down to oyster wenches laboured like pioneers in the trenches.” Another report stated,

“The terror of the citizens, which made a prodigious number of persons of all ranks, ages and sex offer themselves to work, and by unfeigned application in digging, carrying of earth, and other materials soon accomplished their fortification”.

To encourage the work the authorities held book burnings. The volunteers marched out “with roaring drums, flying colours, and girded swords”. Girls cheered as they marched to dig the defences. Almost certainly, religious sermons were used to whip up zeal. The sermon of “Curse ye Meroz” is taken from the sermon preached by Stephen Marshall to Parliament earlier in 1642. It would seem well suited to the occasion and may have been reused.

Ultimately, the Lines of Communication were to include a ditch and bank 11 miles long. With 23 forts, it surrounded London, Westminster and Southwark.

On its western edge, the line stretched from Vauxhall to a fort on Constitution Hill. This is now within the gardens of Buckingham Palace. A large fort sat at the junction of Piccadilly and Old Park Lane. This site is now occupied by the Hard Rock Shop and RAF Club.

Berkley Square almost certainly marks the next fort. Conduit Street marks the line of the ditch and bank leading North East. It joined a large fort on the high ground at the junction of Oxford Street and Berwick Street, close to Next.

Essex March – Warwick, Daventry, Weedon, Olney, St Albans to London – 1st to 6th November 1642

Essex probably begun his march from Warwick on the morning of 31st October 1642, after Sunday sermons and prayers in Warwick. Daventry is likely to have been the centre of his quarters that night. He was to march from Northampton to Olney on 2nd November.

Essex followed the line of Watling Street (now the A5) with the main body of his army towards St Albans and London. However, he sent a separate, smaller force further South towards Aylesbury. He probably intended it as a flank guard to protect his march. Whatever the intention, this force was to clash with Wilmot just outside Aylesbury. Notes on this skirmish are covered separately at the Battle of Aylesbury.

As late as 1792 the Vicar of Naseby, Northamptonshire, commented that the locals spread dung on the walls of their cottages each year to dry as winter fuel. The practice was almost certainly widespread in cattle grazing areas. It was common in the East Riding of Yorkshire and as late as the Victorian era, visitors to the Isle of Purbeck commented on it. It is also widespread practice across the Middle East and South Asia.

Peace Talks at Colnbrook – 5th to 10th November 1642

Wilmot (not Prince Rupert) occupied Colnbrook on the 5th of November 1642. He stayed at ‘The Catherine Wheel’.(Henry VIII had stayed there in 1516.) It was a key staging post on the highway from Bristol to London.

It was Charles I who formally established the Great Road. This highway was part of the network he laid out across England during his administration. He also established the Post Office. This allowed private individuals to pay to have their letters carried by the Royal Mail.

The King arrived in Colnbrook on the 9th of November. He also stayed at the ‘Catherine Wheel’. It was here that he received the parliamentary peace commissioners the next day. Whilst the talks made some progress, neither side proposed a ceasefire.

Other inns at Colnbrook included the ‘Talbot’, the ‘King’s Arms’ and the ‘George’. (Princess Elizabeth stayed at the George in 1558.) They also included ‘The Ostrich’. This remarkable inn still stands today.

The Ostrich Inn at Colnbrook

The Ostrich Inn at Colnbrook is almost certainly the third oldest inn in England. It has foundations dating to 1106.Originally named ‘The Hospice’, its name has corrupted over the years to ‘The Ostrich’. It is worth a visit.

The Ostrich is the site of one of Britain’s earliest novels. Thomas Deloney wrote and published Thomas of Reading in 1602. Deloney’s story tells how Thomas Cole, a wealthy clothier from Reading, is given the best room at the inn. However, he is murdered when a trap door drops him into a “great cauldron” in the kitchen below.

Other historical visitors to the Ostrich included Dick Turpin. The highwayman used the inn as a hideout. He escaped the Bow Street Runners by jumping out of a window. King John supposedly stopped at the inn on his way to Runnymede to sign the Magna Charta.

Essex Defence of London – 8th to 11th November 1642

Ultimately, Essex beat the King to London. His army limped into the capital on the 6th and 7th of November. By the 8th, Lord Brooke and others were galvanising the population to support the parliamentary cause. His speech at the Guildhall is recorded. Support for Parliament was by no means certain. There were many in the London that now called for peace.

However, events changed dramatically when the King attacked Essex’s outpost at Brentford on the 12th of November. The King’s army captured Brentford Bridge and now directly threatened Westminster. The next day, the city did provide its trained bands who marched out and stood with Essex’s army to defend London at Turnham Green.

More Reading

I hope you found these notes on the campaign for London in 1642 useful. You may also want to read my notes on the Battle of Edgehill. This site also has notes on the Battle of Aylesbury and the Battle of Brentford.

You can also read about Pike and Shot Warfare. This article explains the clash between Dutch and Swedish military doctrines at Edgehill in 1642. More articles on The General Crisis of the 17th Century, including the Wars of Religion and The Thirty Years War, and the Great Rebellion are also at Notes and Maps.

If you want more, you can join the Divided Kingdom Readers’ Club. You will receive a monthly email from me including more notes from my research. If you think this is for you, please do join the Clubmen.

Alternatively, return to the site Home Page for information about Charles Cordell, latest posts and links to books.