Pike and Shot warfare and the clash of Early Modern military theories at the Battle of Edgehill in 1642.

The Early Modern period was one of great change, not least in military theory and practice. The battle of Edgehill was to witness a clash of the two latest military doctrines in 1642. Many English, Scottish, Irish and Welsh fought for the Protestant cause in the endless Wars of Religion and Thirty Years War in Europe. They brought both doctrines back to England.

Pike & Shot – 17th Century Military Revolution

The 17th Century saw a military revolution that dominated warfare for the next two and half centuries. Until their defeat at the Battle of Rocroi in 1643, the Spanish imperial tercios were feared as the finest infantry in Europe. However, smaller linear formations of pike and musket – Pike and Shot – progressively replaced these great squares of pike, shot, sword and buckler.

Inspired by classical Roman tactics, the Dutch reforms of Prince Maurice of Nassau brought greater firepower to bear and strength in defence. King Gustavus II Adolphus of Sweden adapted these tactics further to deliver both firepower and offensive mobility. These two military doctrines were to clash on the field of Edgehill.

Pike & Shot Files, Divisions and Companies

Both the Dutch and Swedish models of Pike and Shot warfare were based around groupings of file, division (section), company, battalion and regiment; organisational structures that persist today in the British Army. At its most basic level, men formed files; one man standing behind another.

A Dutch file consisted of eight men, one behind another in 8 ranks. This depth was designed to withstand a charge of pikes and allow continuous volley fire as each rank of musketeers fired and reloaded. The Swedish model of six ranks only was to be adopted by all as the British Civil Wars progressed. This reflected both a lack of manpower and growing professionalism.

Files were grouped under a corporal to form a division (a section today) of either pikemen or musketeers. In practice, the number of files depended on manning. However, 4 files per division was the ideal. The corporal led his right-hand file, with his lansprizado (lance-corporal) leading the left-hand file.

A standard foot company consisted of one pike and two musketeer divisions. It was a mixed grouping capable of independent operations. In theory, a captain’s company comprised 100 rank and file; 32 pikemen and 64 musketeers (including corporals), 2 drummers, a clerk and an armourer. In practice, most parliamentary companies at Edgehill were closer to 70-80.

Invariably, a significant number of non-combatant followers accompanied every company. These were generally women and boys, often wives and sons, as well as prostitutes and orphans. Nehemiah Wharton writes of ‘our knapsack boys’. It is not clear how many boys followed each company during the British Civil Wars. However, the Spanish expected one boy per file.

Pike & Shot Regiments and Battalions

As today, each foot regiment consisted of a number of companies (generally ten in 1642). The regimental colonel, lieutenant-colonel and major each nominally commanded their own (slightly larger) companies. Captains commanded the remaining companies. Company officers consisted of a lieutenant, an ensign (who carried the company colour with the pikes) and two sergeants (responsible for musket drill).

Although part of a regiment, individual captains held commissions to recruit, equip and maintain their companies. They had to bear the financial risk when pay from king or parliament was inevitably in arrears. In some cases, they were still referred to as private companies. This is key to understanding the apparent ill-discipline of the time, when troops were unpaid and hungry.

On the battlefield, companies grouped together to form a battaile or battalion. The pike divisions massed to form a single stand or block of pikes. The two musketeer divisions of a company formed a plotoon. These deployed to form two wings of shot that normally flanked the pike block.

Pike and Shot warfare theory allowed a fully manned foot regiment to field two battalions. In practice, regiments rarely had the strength to form more than one. Increasingly, as the war progressed, regiments had to be combined to form a single battalion. The minimum strength of a battalion seems to have been about 400, the ideal 600.

Dutch Tertias and Swedish Brigades at Edgehill in 1642

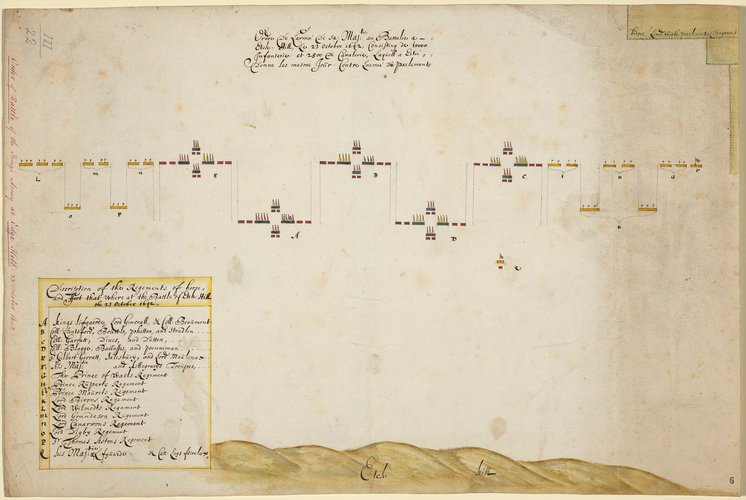

At Edgehill, the parliamentary foot battalions deployed in three Dutch style tertias (thirds). Each tertia consisted of four battalions; one forward, two in second line and a fourth in reserve. The three tertias of a Dutch army deployed in line, vanguard (right), main (middle) and rear-guard (left). Like the Roman quincunx, these formed a checkerboard of battalions in three offset lines.

Prince Rupert had studied Gustavus’ tactics. Under his influence, the King’s foot deployed in 5 (smaller) Swedish style brigades. These also consisted of four battalions in diamond formation. However, these battalions were considerably smaller than those of Essex’s army. De Gomme’s map of the royalist deployment shows the King’s foot clearly, in tighter offensive (attack) formation. The fourth pike blocks have closed up and the musketeer wings have dropped back, in reserve.

Horse Troops, Squadrons and Regiments

As was normal for the period, at Edgehill, brigades of horse deployed on the flanks of each army. De Gomme shows the King’s horse drawn up in two lines of squadrons, each of two to three troops. The parliamentary horse seem to have operated as individual troops. On their left flank plotoons of musketeers deployed between troops of horse.

In theory, a troop of horse consisted of 72 rank and file (69 troopers and 3 corporals). These made up three divisions, under a captain, a lieutenant and a cornet. However, numbers were often in the mid-forties. The files of an English horse troop were, in theory, six deep. However, civil war troops generally drew up in half files of three deep for battle. The order of precedence between the ranks was: 1, 3, 2.

More Reading

I hope you found this article on Pike and Shot warfare at Edgehill useful, how the Dutch and Swedish military doctrines came to clash. Today, you can see this form of warfare regularly re-enacted in UK by the Sealed Knot, the English Civil War Society and the Pike & Shot Society. Other 17th Century re-enactment groups exist across Europe and in the USA.

This website also includes pages on the causes of conflict in the 17th Century and a number of English Civil War battles. You can read about The General Crisis, its impact globally in the 1640s, as well as The Thirty Years War, Wars of Religion and British Civil Wars in 17th Century Europe. You can also read about the crisis facing Early Modern Britain in the 1640s, the English Revolution and the Great Rebellion of 1642.

More articles can be found on the Battle of Edgehill, the Battle of Aylesbury, the Battle of Brentford and the Battle of Turnham Green in 1642, and more. These pages provide historical notes to accompany the text of God’s Vindictive Wrath, which includes accounts of all these battles. There is also a FREE short story to download set during the Storming of Winchester and desecration of its cathedral, entitled To Cleanse Judah.

If you want more, please consider joining the Divided Kingdom Readers’ Club. You will receive a monthly email from me including more notes from my research. If you think this is for you, please do join the Clubmen.

Alternatively, return to the site Home Page for information about Charles Cordell, latest posts and links to books.