The battle of Edgehill was fought on the 23rd of October 1642. It was the first major battle of the English Civil War. Many had anticipated a single show of force or token battle – a letting of blood to ‘purge the nation’. But Edgehill left many in shock. Descending into a brutal drawn-out slog, with no conclusive ending, there was no doubt that war had arrived in Britain.

This page aims to provide historical notes to accompany God’s Vindictive Wrath by Charles Cordell. The notes are listed in order matching the text and cover the battle of Edgehill. This website includes more notes to later sections of the novel.

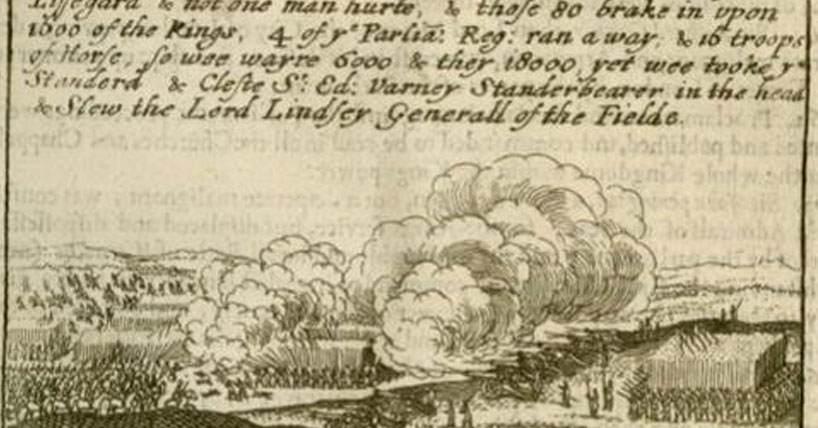

The Edgehill Battlefield in 1642

Edgehill marks the boundary between the high rolling Oxfordshire plateau and the lower lying plain of Warwickshire. On a clear day, you can see as far as the Malvern Hills, on the border of Herefordshire. You can see Bredon Hill and the towers of Worcester Cathedral. The spires of Stratford upon Avon, St Mary’s Warwick and Coventry Cathedral are also visible.

In 1642, the parishes to the north and south of Radway and Kineton (including Burton Dassett and Tysoe) had begun the process of enclosure. This formed the network of smaller fields and hedges we see today. However, Radway and Kineton retained their large open medieval fields and commons.

We also know that Edgehill itself had far fewer trees on its slopes in 1642. The woods we see today were planted out in the 18th Century. Almost certainly, the battle was fought across the open fields of Radway and Kineton. The initial skirmishes on the flanks would have been to clear the early enclosures on the fringes of Burton Dassett and Tysoe.

Clarendon described the weather on the day of the battle of Edgehill in his account of the Civil War, The Great Rebellion. ‘It was as fair a day as that season of the year could yield, the sun clear, no wind or cloud appearing.’ Parliamentarian accounts agree, but state that the King had the advantage of the wind. This suggests a slight easterly or north easterly breeze.

Hugh Peters and the Vale of the Red Horse

Before the battle of Edgehill, Chaplain Hugh Peters (1598-1660) rode ‘from rank to rank with a bible in one hand, and a pistol in the other, exhorting men to do their duty’. This ‘worthy divine’ had recently returned from New England where he was the preacher at Salem. He was later one of the regicides that signed the death warrant for King Charles I.

The battlefield of Edgehill lies within the Vale of the Red Horse. The significance of this fact and its link to the Biblical Red Horse of Revelations was not missed in 1642. Its image of War and the End of Times was clear. Chapter 17 gave added resonance to those opposing the King. It included ‘the whore of Babylon’ “with whom the kings of the earth have committed fornication, and the inhibiters of the earth have been drunk with the wine of her fornication.”

The sermon in God’s Vindictive Wrath is based on John Vicars, Jehovah Jireh, God on the Mount, (Vol 1 of England’s Parliamentary Chronicle, 1643). It was preached in London shortly after Edgehill. However, it provides a good example of the puritanical zeal and reference to scripture fundamental to so many. Similar words, or an earlier version, may well have been spoken on the morning of the battle.

The Red Horse of Tysoe

The Red Horse of Tysoe is no longer visible. However, it is known to have been cut into the red earth on the slope above the Sun Rising Inn. It is described in at least one 19th Century account as being of ‘colossal dimensions’. It was visible from Lower Tysoe village.

William Dugdale described the Red Horse in 1656. Celia Fiennes also described it in 1698 in Through England on a Side Saddle in the Time of William and Mary. It was still visible in 1841, described by Alfred Beesley in his The History of Banbury.

Almost certainly cut as a Celtic horse, we know that it was recut in 1461, after the battle of Towton. Tradition has it that the Earl of Warwick killed his own horse during the slaughter at Towton. He vowed to share the danger with his foot soldiers.

The people of Tysoe cleaned the Red Horse every Palm Sunday. This essential regular scouring ceased with enclosure of the common land on which it was cut in 1798.

The King’s Army at Edgehill

Clarendon gives a clear comparison of the state of the two armies at Edgehill. He says of the King’s Army,

“The greatest difficulty was to provide arms – of which indeed there was a wonderful scarcity. … But in all places the noblemen and gentlemen of quality sent the king such supplies of arms out of their own armouries (which were very mean) that by all these means together, the foot (all but three or four hundred who marched without any weapon but a cudgel) were armed with muskets, and bags for their powder, and pikes; but in the whole body there was no one pikeman had a corselet, and very few musketeers who had swords. Amongst the horse, the officers had their full desire if they were able to procure old backplates and breastplates and pots [helmets] with pistols and carbines for their two or three first ranks, and swords for the rest.”

The Parliamentary Army at Edgehill

We know that Parliament had secured most of the arms and armour held by the county trained bands. It had also prepared a number of regiments under the pretext of sending them to quell the rebellion in Ireland. As a result, Essex’s foot was better equipped and uniformed. The King’s foot had to rely on personal armouries donated by individuals. Clarendon tells us that,

“Within two days after the king marched from Shrewsbury, the Earl of Essex moved from Worcester to attend him, with an army far superior in number to the king’s; the horse and foot being completely armed, and the men very well exercised, and the whole equipage (being supplied out of the king’s magazines) suitable to an army set forth at the charge of a kingdom.”

Many of the parliamentary foot were religiously or politicaly motivation. However, Sergeant Nehemiah Wharton of Holles’ Regiment describes others.

“The ruder sort of soldiers, whose society, blessed be God, I hate and avoide … many of them discovered their base end in undertaking this design, and demanded five shillings a man, which they say was promised them monthly by the Committee”.

No doubt, both armies at Edgehill included of the mix of choir boys and rogues that has characterised every British army since.

The Deployment of the Two Armies

The exact disposition of each army at Edgehill remains a point of debate. However, we can draw on the contemporary accounts and de Gomme’s map of the royalist order of battle. We can also apply realistic battalion and brigade frontages. Finally, we should apply these to the parish boundaries, archaeological evidence and a military appreciation of the ground itself.

It is clear that Essex marched out from Kineton on the morning of 23rd October. He deployed his army in line along the low ridge feature that runs north east from the Oakes. We know that the Parliamentary foot was drawn up in three tertias (brigades).

The Parliamentary Foot Deployment

On the Parliamentary right stood their ‘Vanguard’, under Sir John Meldrum. This included the regiments of Lord Robartes (‘redcoats’ from Bucks), Lord Saye (Oxon ‘bluecoats’), Sir William Constable (Yorks blue) and Sir William Fairfax (Yorks).

The ‘Battle’ or centre was commanded by Charles Essex. The official Parliamentary account clearly places his tertia “in the middle”. It contained the regiments of Lord Wharton (black colours), Lord Mandeville (green), Sir Henry Cholmley (London blue) and Charles Essex’s own (tawny yellow).

On the left stood the ‘Rearguard’ under Thomas Ballard. This included the Earl of Essex’s (from Essex in orange), Lord Brooke’s (London and Warwickshire in purple), Ballard’s (Bucks grey) and Denzil Holles’ (London red) regiments.

The term ‘rearguard’ in no way suggested that this formation fought in a second line. It simply referred to its position in the line of march. It is likely that Essex’ foot marched out of Kineton on the road towards Knowle End and swung south onto its battle line. This placed the three tertias in line abreast.

The line of Parliamentary foot probably extended along the low rise from the spot height south of King John’s lane. (This is centred on OSGB Grid References SP 351490.) It almost certainly extended to the Knowle End road (SP 358503), with Holles’ Regiment beyond that.

The Parliamentary Horse

The Parliamentary right wing of horse was probably stationed on the high ground that is now the Oakes (SP 345488). A skirmish line of dragoons deployed forward and right in the “briars”. This rough ground almost certainly marked the Kineton and Tysoe parish boundary.

The Parliamentary account describes Ramsay’s horse being on a small hill, “advanced a little”, forward and left of the foot. Essex left wing of horse probably occupied the rise north of the Kineton to Knowle End road (centred on SP 363506). Musketeers plotoons were deployed between the horse troops. They were also stationed in the enclosures along the parish boundary between Radway and Barton Dassett.

The King’s Horse

Rupert’s horse probably faced Ramsay from a position that was also north of the Kineton to Knowle End road. This would be around Arnold’s Farm (SP 378497). Recent surveys, archaeological finds and re-examination of the battlefield suggest that the battlefield extended further north than previously thought.

Lord Henry Wilmot, Earl of Rochester, Commissary General of Horse commanded the left wing of the King’s horse at Edgehill. He had been wounded, in the arm, at Powick Bridge. His brigade was probably a little over 1,000 strong. It consisting of his own regiment with those of Lord Grandison, the Earl of Carnarvon, Sir Thomas Ashton and Lord Digby.

The day before Edgehill, Lord Digby had been ordered to find the enemy. He reported that there were none. However, that evening, quartermaster parties of Essex and Prince Rupert clashed in the village of Wormleighton. Each was scouting for accommodation for their troops. Those of Essex were taken prisoner.

On the morning of 23rd October, Lt Clement Martin (with 24 men of Prince Rupert’s Regiment of Horse) confirmed that Essex was at Kineton. Lord Digby’s regiment was placed in the least dignified position in the order of battle, in reserve at rear left. This was almost certainly a mark of his failure the day before.

Captain John Smith

Captain John Smith (a brother of Lord Carrington) already had a reputation as a man of honour and action. Walsingham described his fierce appearance as “Rather formed to command Armies than allure Ladies”. Smith was not a stereotype cavalier. He was no gallant. Short in stature and charm, and even shorter in words. Generous to his troopers, he was as a perfect knight. He could not stand bullies and thrashed a soldier who had abused prisoners taken at Hull. A billeting officer extorting money from the citizens of Leicester was flung on a dung heap. He was fatally wounded at Alresford (Winchester). Edward Walsingham later praised him as, “Of one whose fame can never rust That noble, gallant knight Renowned Smith …”

In contrast, Smith’s commander, Lord John Stuart was a gentleman of ‘wonderful sweet and noble disposition’. He was a cousin of Charles I and brother to the Duke of Richmond and Lennox. His second brother, Lord Bernard Stuart, commanded the King’s Lifeguard of Horse. Van Dyke’s painting of these cavalier brothers hangs in the National Gallery. Both were to be killed in the Civil War, in 1643 and 1644.

The King’s Foot

De Gomme (the King’s Engineer) provides a clear diagram of the King’s deployment at the start of Edgehill. We also know the constitution of his five foot brigades.

The right was commanded by Charles Gerard. With him were Sir Lewis Dyve’s, Sir Ralph Dutton’s (Gloucestershire ‘whitecoats’) and his own (Lancs ‘bluecoats’, Cheshire & North Wales). John Belasyse stood with Sir William Pennyman’s (Yorks), Thomas Blagge’s (Suffolk) and his own (Yorks & Notts).

In the centre Richard Fielding lead the largest brigade. This included Sir Thomas Lunsford’s (Somerset), Sir Edward Fitton’s (Cheshire) and Sir Edward Stradling’s (South Wales). With them were Richard Bolle’s (Staffs) and Fielding’s own (Hereford).

Sir Nicholas Byron marched with the King’s Lifeguard of Foot (Lincs, Derby & Cheshire). With him were the Lord General’s (Lincs) and Sir John Beaumont’s (Staffs). Henry Wentworth commanded the left. This included Lord Molineux’ (Lancs), Sir Gilbert Gerard’s (Lancs) and Sir Thomas Salusbury’s (North Wales).

Almost certainly, Graveground Coppice (SP 353492) marks a point close to the most intense fighting. It is close to the greatest concentration of casualties. These were centred on the fight for the Royal Standard, between the King’s Lifeguard and Constable’s. It is unlikely that the dead were moved far.

Assuming this is true, it would make sense that Byron’s brigade advanced with King John’s lane as its left boundary. Their start point would have been forward of the old (1642) church of Radway (at SP 369478).

This would place Wentworth’s brigade south of the lane. Wilmot’s left wing of horse were beyond them. Again, this would seem to make sense. Their charge met broken ground and the briars along the parish boundary.

Charles I and his Lifeguard of Foot at Edgehill

Sir Richard Bulstrode’s account of the battle provides a description of Charles I at Edgehill. ‘The King was that Day in a black Velvet Coat lin’d with Ermin, and a Steel Cap covered with Velvet. He rode to every Brigade of Horse, and to all the Tertia’s of Foot, to encourage them to their Duty, being accompanied by the great Officers of the Army; His Majesty spoke to them with great Courage and Chearfulness, which caused Huzza’s thro’ the whole Army.’

The King’s speech in God’s Vindictive Wrath is based on that recorded in, Three Speeches made by the King, ‘The King’s Majestie’s Speech to his Whole Armie immediately before Battell’, London, 1642, Thomason Tract, E200 (67). The King’s words to his principal officers are also taken from this source and based on his address to them that morning.

In the summer of 1642, Charles I accepted the offer of a delegation of free-miners from the Derbyshire High Peaks to form a lifeguard. This was in exchange for the abolition of the hated lead tithe. By early September, 400 miners had mustered at Derby. They formed the nucleus of the King’s Lifeguard of Foot. We know the names of many of those that mustered, some from the village of Castleton.

The King’s Lifeguard of Foot were to go on to fight throughout the first Civil War. One remnant of the regiment finally surrendered at Tresillian Bridge outside Truro in Cornwall in 1646. Although not a direct descendant, the Grenadier Guards trace their lineage to the King’s Lifeguard of Foot reformed under Charles II at Bruges in 1656.

The Parliamentary Bombardment

The best of Essex’s artillery was near his right centre. According to Edmund Ludlow, Essex ordered them to fire. “Our general having commanded to fire upon the enemy, it was done twice upon that part of the army wherein, as it was reported, the King was. The great shot was exchanged on both sides for the space of an hour or thereabouts. By this time the foot began to engage.”

The first casualty at Edgehill was Lieutenant Francis Bowles of Fielding’s Regiment. We know that his arm and shoulder were shattered in the bombardment that opened the battle. Although he lost the use of his arm, he went on to serve at Bristol and Naseby.

The King’s Speech

The King’s generals refused to march until the King had withdrawn to a place of safety. We do not know exactly where this incident took place or exactly what was said. However, it is likely that Sir Jacob Astley, as Sergeant-Major General, took a place close to the King’s Banner Royal. This was with the Lifeguard of Foot, on the right of Sir Nicholas Byron’s Brigade. It was a position close to the centre of the line and well-marked. The King almost certainly wished to march with his Lifeguard. It is, therefore, likely that this incident took place in front of that regiment.

We do not know what was said. However, we do know from Bulstrode that the King had already addressed his principal officers in his tent on top of Edgehill. It seems probable that he expressed similar sentiment with them before they forced him to withdraw.

“If this day shine prosperous unto us, we shall be happy in a glorious victory. Your King is both your cause, your quarrel, and your captain. The foe is in sight. You shew yourselves no “malignant party”, but with your swords declare what courage and fidelity is within you. I have written and declared, that I intend always to maintain and defend the Protestant religion, the rights and privileges of Parliament, and the liberty of the subject, and now I must prove my words by the convincing argument of the sword. Let Heaven shew his power by this day’s victory, to declare me just; and, as a lawful, so a loving King to my subjects. The best encouragement I can give you is this; that come life or death, your King will bear you company, and ever keep this field, this place, and this day’s service in his grateful remembrance.”

John Lilburne, Lord Brooke’s Levellers and Psalm 149

John Lilburne was already a well-known political hero. In the summer 1642 he sold his brewery business to become a captain in Lord Brooke’s Regiment. “As ready and willing to adventure my life as any man I marched along with.” He later described his actions. “I scorned to be so base as to sit down in a whole skin … while the liberties and freedoms of the kingdom was in danger.” He was accompanied by his wife during much of his campaigning.

Lord Brooke’s Regiment was brigaded with those of the Earl of Essex, Thomas Ballard and Denzil Holles. Together, they formed Thomas Ballard’s ‘Rear Guard’ Tertia. As the second senior colonel, Lord Brooke’s regiment was likely to take its place the left of the brigade. This would put it just south of the Kineton to Knowle End road (SP 358503).

Richard Elton, in his The Compleat Body of the Art Military, clearly shows the positions of dignity of each battalion of a brigade. The senior takes the right, second left, third centre and fourth in rear. Denzil Holles, as junior was almost certainly in brigade reserve. His battalion was probably drawn out to the left flank, behind Ramsey’s wing of horse.

The singing of psalms was repeatedly used to steel the nerve of Parliamentary regiments. Psalm 149 was a favourite with Lord Brooke’s Regiment. We know they sang it as they stormed Lichfield Cathedral Close in March 1643. Its sentiment must have appealed to John Lilburne and the levellers who “marched along with” him. They would have delighted in its call “To bind their Kings with chains. And their nobles with fetters of iron.”

The King’s Battery at Edgehill

The King’s battery at Edgehill included: two demi-cannon (27lb ball), two culverins (15lb ball) and two demi culverins (9lb ball). Two to three smaller guns were placed with each foot brigade.

A Gentleman of the Ordinance was responsible for each pair of guns. Those detailed for Banbury were: Mr Henry Speed and Mr William Snedall (two demi cannon and two culverins), Mr William Stone and Mr Merritt (two demi-culverins and two falcons). Conductor Cuthbert Cartington was present at Edgehill. He died of his wounds at Yarnton on 31 Jan 1644. We also know the name of at least one gunner, Mr Nicholas Busy.

The ‘Cold Gun Effect’ tends to throw the first few projectiles of an artillery piece long. The cold barrel is slightly shrunk and reduces the ‘windage’ between barrel wall and projectile. As a result, the propellant gasses act more forcefully upon the projectile imparting greater muzzle velocity. Edmund Ludlow (with the Earl of Essex) states that the King’s cannon “did no harm”.

“For being so much upon the descent his cannon either shot over, or if short it would not graze by reason of the ploughed lands: whereas their cannon did some hurt having a mark they could not miss. Prince Rupert did not let them long dally with great shot”.

Rupert’s Charge and Nehemiah Wharton

The official Parliamentary account of Edgehill describes Rupert’s charge. “Our Left Wing of Horse, advanced a little forward to the Top of a Hill, where they stood in a Battalia, lined with commanded Musketeers, 400 out of Col. Holles’s Regiment, and 300 out of Col. Ballard’s; but upon the first Charge of the Enemy, they wheeled about, abandoned their Musketeers, and came running down with the Enemies Horse at their Heels, and amongst them pell-mell,

“Just upon Col. Holles himself, when he saw them come running towards him, went and planted himself just in the way, and did what possibly he could do to make them stand; and at last prevailed with three Troops to wheel a little about, and rally; but the rest of our Horse of that Wing, and the Enemies Horse with them, brake through and ran to Kineton, where most of the Enemy left pursuing them, and fell to plundering our Wagons.”

We know of Nehemiah Wharton, a London apprentice, through his letters. He wrote regularly to his master care of the Golden Lion on St Swithin’s Lane. His letters stopped abruptly just before the battle of Edgehill. As a sergeant in Denzil Holles’ Regiment, his place was with a plotoon of musketeers. He may well have been with one of the commanded plotoons with Ramsay’s horse, ridden down by Rupert.

Wilmot’s Charge and Digby’s Pursuit

The King’s left wing of horse, under Wilmot, also swept away its opposite wing. Like Rupert, most of this wing fell to plundering Essex’s baggage train in Kineton.

Critically, however, they were followed by the King’s reserve of horse under Lord Digby. This reserve should have exploited the situation by falling on Essex’s foot. More importantly, it left the King’s foot without support.

There are references to John Smith persuading senior officers to rally in support of the King’s foot after Digby charged. These included his colonel, Lord Grandison as well as Colonel Lucas. See Edward Walsingham’s Account of the Doings of Sir John Smith.

Just outside Kineton, the Tysoe road passes the Dene River. Bodies and pieces of armour were discovered here around 1750. These were on the site of the old ford, immediately south of the 19th Century bridge. Sanderson Miller (who planted the ‘hanging woods’ on Edgehill) gives an account of their discovery.

Panic Fear – the Collapse of Essex’s Centre

The spread of fear and consequent collapse of cohesion within an armed force was known in the 17th century as “a panic fear”. The official Parliamentary account of the battle describes Charles Essex’s centre tertia as collapsing without firing a shot. Some recent works on the battle have tried to place Essex’s Tertia in the way of Rupert’s charge. However, it is often troops that are not directly in the line of an assault that break first. They simply break from fear, rather than the actuality of combat. The Parliamentary account is clear that Charles Essex’s tertia broke without being charged.

“At the very first wholly disbanded and ran away, without ever striking a stroke, or so much as being Charged by the Enemy, though Col. Essex himself, and others, who Commanded these Regiments in Chief, did as much as Men could do the stay them; but Col. Essexbeing forsaken by his whole Brigade, went himself into the Van, where both by Direction and his own Execution, he did most gallant service, till he received a shot in the Thigh, of which he is since dead.”

Closing the Gap – Essex’s and Brooke’s Move to the Right

The official Parliamentary account goes on to explain that after the collapse of Essex’s centre, Ballard’s left-hand tertia “marched up the Hill, and so made all the haste they could to come to the fight”. This is almost certainly the slight rise south along the Parliamentary line to Graveground Coppice. The account describes how they “came on … most gallantly, and Charged the Enemy, who were then in fight with our Van, and the Right Wing of our Horse”.

The account specifically mentions Lord Brooke’s Regiment. It moved along the Parliamentary line, to its right. “When our Rear came up … especially that part of our Rear which was placed upon the Right hand, and so next unto them [the Van] which was the Lord General’s Regiment, and the Lord Brook’s, led on by Col. Ballard”.

The Advance of the King’s Foot

Sir Jacob Astley’s short soldier’s prayer and brief order are recorded. They seem typical of this experienced old soldier. Drums in every company would relay his orders for the King’s foot to advance.

Richard Elton writes of musket shot passing through an advancing stand of pikes. His The Compleat Body of the Art Military describes the sound. “The bullets would make such a chattering amongst the Pikes, that what with breaking of them, and the shivers flying from them, may much endanger the Soldiers which shall carry them”.

The shouting of insults between units was commonplace. Unless soldiers have changed dramatically, much of this would have been sexual in nature. Royalists, and Catholics in particularly, were accused of sexual licence. The term ‘bugger’ referred to both heretical thought and sodomy. A “shitten lobcock” is a misshapen penis that is covered in shit.

Push of Pike

James II gives us a good account of the fighting. “When the royall army was advanced within musket shot of the enemy, the foot on both sides began to fire, the king’s still coming on and the rebell’s continuing only to keep their ground, so that they came so near to one another that some of the batalions were at push of pike, particularly the regiment of Guards commanded by the Lord Willoughby and the general’s regiment [Lindsay’s], with some others; insomuch that the Lord Willoughby with his pike killed an officer of the Earl of Essex his regiment, and hurt another.

“The foot being thus engaged in such warm and close service, it were reasonable to imagine that one side should run and be disordered; but it happened otherwise, for each as if by mutuall consent retired some paces, and then stuck down their colours, continuing to fire at each other even till night, a thing so very extraordinary as nothing less than so many witnesses as were there present could make it credible.”

Sudden, uncontrolled vomiting is not an uncommon reaction to the first act of killing, even amongst experienced soldiers. This will normally occur once the immediate danger and adrenalin has passed.

The Charge of the Parliamentary Reserve of Horse

Sir William Balfour commanded the two reserve regiments of horse, his own and Stapleton’s. The latter included a number of troops of cuirassier, including Essex’ Lifeguard of Horse. The two regiments appear to have been launched through the gap left by Charles Essex’ Tertia. Stapleton attacked the Sir Nicholas Byron’s (left centre) brigade and was initially repulsed. Balfour broke Fielding’s (centre) brigade and rode on to the King’s battery. He is described as breaking a Regiment of Foot with green colours.

Once broken, fleeing foot soldiers were vulnerable to appalling injury from pursuing horse. The royalist surgeon Richard Wiseman (in his Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, London, 1676) provides a vivid account of the wounds inflicted on fleeing foot during the Civil War: ‘when the Horse-men fall in among the Infantry, and cruelly hack them; the poor soldiers the while sheltering their heads with their arms, sometime with the one, sometime with the other, until they both most cruelly mangeled; and yet the head fareth little the better for their defence, many of them not escaping with less than two or three wounds through the skull to the membrane, and often into the Brain.’

We know from contemporary accounts that a charge by Stapleton’s regiment of horse forced the musketeers of the Lifeguard and the Earl of Lindsey’s Foot to “shrowd themselves within their pikes, not daring to shoot a shot”. The Royalist musketeers had almost certainly expended their ready supply of shot and powder. Essex’s Lifeguard of Horse (equipped as cuirassier under Sir Philip Stapleton and including one Edmund Ludlow) charged the King’s Lifeguard of Foot. They received some loss from pike but few from shot. However, they could not break the Lifeguard and withdrew to their former station on the ridge.

Essex Turns on the King’s Lifeguard

Exploiting the gap in the King’s centre, Essex ordered Ballard to attack Sir Nicholas Byron’s Brigade. He did this with Lord Brooke’s and the Lord General’s regiments. The King’s Lifeguard was already locked in combat with Constables. It is likely that Ballard attacked their exposed right flank. To do this, they would need to wheel their frontage through 90 degrees. This manoeuvre would have pivoted about the right-hand marker. It would have been conducted at the order, 3 feet between rank and file.

The King’s Horse Destroy Essex’s Centre – Lucas’ Charge

As they moved towards the rear of Essex’s Army, Lucas and Grandison’s force met with Charles Essex’s brigade in rout. Edward Walsingham describes the encounter in his ‘Doing’s of Sir John Smith’.

“In their passage they met with a great part of the Rebels of Charles Essex his Regiment [brigade], running confusedly towards Kineton Towne with their colours: those they presently charged, slew some, routed the rest and took all their Colours.”

Balfour’s Charge Against the King’s Battery

Having broken a regiment of foot with green colours, almost certainly Fielding’s, Balfour’s Horse overran the King’s battery. His horsemen cut down many of the King’s gunners. Carlton states that this was done from hatred of gunners. Many saw them as fiends and the guns as devilish machinations.

Balfour called for nails, to spike the guns, but could find none. He then cut the ropes, the ‘traces’ that formed part of the horse harness of the gun teams. The only sensible reason to do this would be to prevent the guns’ removal from the battlefield. It may well be that gun teams were brought forward and an attempt made to remove some of the guns from the battlefield. It probably seemed that the battle was lost.

Brigadier Young’s analysis of the Ordnance Papers concludes that the King’s battery fired 16 rounds of case-shot at Edgehill. He suggests that this short-range ammunition was fired in the closing moments of the battle, against the Parliamentary foot. However, it would seem equally, if not more plausible that it was used against Balfour’s charge. It is what it was designed for.

Those gunners who escaped Balfour’s troopers probably sheltered amongst the baggage train. Captain William Legge’s Company of Firelocks guarded it. These were men armed with an early form of flintlock musket. They guarded the baggage train as they did not carry lighted matches.

The Last Stand of the Lifeguard

Essex ordered Ballard to attack Sir Nicholas Byron’s Brigade with Lord Brooke’s Regiment and the Lord General’s Regt. The Lifeguard was already locked in combat with Constables. However, they could not break them until Essex’s horse added their weight.

Balfour charged Byron’s brigade in the rear, almost certainly on his return from overrunning the King’s battery. Stapleton attacked Byron’s flank (presumably the left flank). According to the Parliamentary account, the action broke both the Lifeguard and Lord General’s (Lindsey’s) regiments. Balfour captured a number of Lifeguard company colours and left the Lifeguard mauled.

At this point, the King’s Banner Royal was also captured. This was the standard that had called loyal subjects to the King earlier that summer. It was the embodiment of his cause.

Sir Edmund Verney, the King’s Knight Marshal

Sir Edmund Verney was the King’s Knight Marshal. He carried the Banner Royal within the ranks of the King’s Lifeguard of Foot. Sir Edmund had served Charles I since their farcical trip to Madrid in 1623 (to woo the Infanta). He fought for the King out of a sense of duty. However, his writing suggests that his belief in the cause may not have been so strong.

“My conscience is only concerned with honour and gratitude for to follow my master. I have eaten his bread and served him near thirty years, and will not do so base a thing as to forsake him, and choose rather to give my life – which I am sure I shall do.”

Sir Edmund Verney was a proud man, but one ridden with gout. He was deeply in debt, with five unmarried daughters (Pen, Peg, Molly, Cary and ten year-old Betty). His eldest son (Ralph) had sided with Parliament, his second son (Tom) was a wastrel, while his third (Edmund) served in Ireland. His portrait is of a deeply lined and troubled face. Three years before, Sir Edmund had written to Ralph, on his way to the disastrous Bishops’ War against Scots Covenanters.

“For my own part I have lived till pain and trouble has made me weary to do so; and the worst that can come shall not be unwelcome to me; but it is a pity to see what men are like to be slaughtered here. … I am infinitely afraid of the gout, for I feel cruel twinges, …”

His son described Sir Edmund in his letters. “Has the vain hope of a little fading honour swallowed up all your good nature?” “I know his courage will be his destruction; no man did ever so wilfully ruin himself and his posterity.”

The Banner Royal Taken

Sir Edmund Verney wore neither armour nor buff-coat. He seems to have had a premonition of death. Before he was killed by Ensign Arthur Young, “[he] killed two with his own hands, whereof one had killed poor Jason, and broke the point of his standard at push of pike before he fell.”

Verney’s hand was hacked off, still holding the standard. On the hand was a small ring with a miniature portrait of his sovereign. By the end 60 bodies lay within a radius of 60 yards from King’s standard. Almost certainly they lie buried close to where they fell, in Graveyard Copes.

The Return of the King’s Horse

Having cut their way through most of Essex’s fleeing centre, some of the King’s horse returned to the battle. They encountered and charged three troops of parliamentary horse. This must have been Balfour’s Horse as they retook some of the Lifeguard’s lost colours.

Soon after, Smith “could rally but fourteen men together to prosecute his return: with which as he passed up still towards the rear of the Rebel’s Army, he met with a great part of the Lord Wharton’s Regiment”. This was probably the last remnant of Charles Essex’s centre tertia trying to reform.

“With his fourteen horse he valiantly charged and routed them took their Colours. The Major’s Colours were taken by himself, which he delivered to one Chichley a groom of the Duke of Richmond’s, who had taken a Colours of Charles Essex his Regiment.”

The Retaking of the Banner Royal – John Smith

Edward Walsingham’s Account of the Doings of Sir John Smith describes the route of Charles Essex’ tertia and Balfour’s Horse. It also covers the breaking of Wharton’s Regiment with ‘but fourteene men’ and the retaking of the Banner Royal. How ‘a boy on horsebacke’ pointed out the Standard to Smith and Chichley. It describes Smith’s response, fight with the escort and wounding.

An alternative version is given in Edmund Ludlow’s Parliamentary account of the battle. Ludlow suggests that the Standard was handed over after a deception to “Captain Smith, who, with two more, disguising themselves with orange-coloured scarfs”.

Accounts also vary as to how long the standard was in parliamentary hands. Captain Edward Kightley stated that the banner was in parliamentary hands for an hour and a half. Others suggest just six minutes. It was probably somewhere in between. Either way the significance of its loss and recapture cannot be mistaken.

The End of Battle – John Benion and the Powder Keg

Local oral tradition provided an account of the battle, recorded in 1833, worth relating. ‘The King was on the hill here; the others came Kineton way. They fought in tow companies; one along the hill at Bullet Hill, where the road comes up; but the main in the vale at Battleton and Thistleton [farms]. They on the hill drove the others down into Kineton; whilst they at Battleton and Thistleton made head, and forced the King back to the hill.’ This is taken from Alfred Beesley, The History of Banbury, London, 1841.

Sir Richard Bulstrode tells us that, ‘The night came soon upon us … And, to add to our misfortune, a careless Soldier, in fetching Powder (where a magazine was) clapt his Hand carelessly into a Barrel of Powder, with his Match lighted betwixt his Fingers, whereby much Powder was blown up, and many kill’d.’ It is not known who was responsible. But it was almost certainly a hurried, careless or frightened soldier.

Richard Gough’s The History of Myddle tells us that John Benion, a tailor from the village of Newtown in Shropshire, left to join the King’s army. He never returned. He is assumed to have been killed at Edgehill. His wife, Elizabeth, died shortly after.

Many rural tradesmen suffered from the downturn of the woollen cloth industry. At the same time, enclosure removed rights to grazing and foraging on common lands. Pay of 14 groats a week must have been attractive to these men. There is no evidence to suggest that John Benion was not a model soldier. However, men enlist for a multitude of reasons and some never overcome their fear.

The Night After – Aftermath

The night of 23rd October 1642 was almost certainly clear, following a cloudless day. We know that there was a harsh frost. Many commentators spoke of it. It is likely that this was accompanied by mist or fog a few hours later.

We also know that there was near full moon that night. It would have provided almost continuous light from sunset. A ‘Hunter’s Moon’ would be full on 27th October 1642. In England (at a latitude of 40o north) the narrow ecliptic orbit provides bright moonlight in October and November, from sunset until midnight. Harvest and Hunter’s moons traditionally allowed farmers and hunters to work late into the night in preparation for the winter.

Dread Night – The Dead and the Dying

However, at Edgehill the night was marked by a terrible groaning of wounded. “A great deal of fear and misery” wrote one trooper of the night. How a man died was considered important. His state at death was an indication of whether he was bound for heaven or hell. Dying well was considered important. Moaning and wailing were not signs of a good death.

Essex had probably lost approximately 1,000 dead and many more deserted. The King lost around 500, with only 50 from his horse. Many troops were probably mixed up and still trying to get back after their charge.

The parliamentarian Edmund Ludlow recounted, “It was observed that the greatest slaughter on our side was of such that ran away, and on the enemy’s side of those that stood; of whom I saw about threescore lie within the compass of threescore yards upon the ground whereon that brigade fought in which the King’s standard was.” It is very likely that these bodies were buried close to where they fell. Almost certainly this is now Graveground Coppice Wood.

Essex foot spent the night of 23rd October on the field of Edgehill. They were drawn up in formation in the positions they occupied. In the early morning they realised that the King’s Army had all withdrawn up the hill and so they withdrew to Kineton.

The old church of Radway became a Royalist field hospital. There is a tradition that a local woman, Elizabeth Heritage, acted as a nurse. Radway Church was originally near the village pond. It was moved to its new site a century after the battle. The monument to Captain Henry Kingsmill, killed serving the King, was also moved. Radway Grange was owned by the Washington family, linked to the first President of the USA.

The Burton Dasset Beacon

At least one account tells that the Parliamentary army lit a beacon on the night of Sunday 23rd October 1642. This was a pre-arranged signal to London that they had met and fought the King. The signal was sent from the stone Beacon House at the north western tip of the Dassett Hills.

Tradition has it that shepherds at Ivinghoe, 40 miles distant on the Buckinghamshire and Hertfordshire border, saw the light. They reported it to their local minister who fired a similar beacon. Watchers at Harrow on the Hill saw it and conveyed a message to Parliament. The Beacon House at Burton Dassett is still standing and is visible from the M40. Its 5 foot diameter iron fire cresset was kept in the church for many years. For more, see Alfred Beesley, ‘The History of Banbury’, London, 1841.

The Clenching of Teeth and Comenius’ Lullaby

The clenching of teeth in combat is a natural phenomenon. It is particular amongst those facing battle for the first time. After battle, the muscles relax. Jaws often fall open in what has been mistaken for an idiot’s grin. Both reactions were widely recorded during WW2, in Normandy and Burma. Edmund Ludlow recalled that, after Edgehill, he struggled to eat a piece of bread. “I could scarce eat it, my jaws for want of use having lost their natural faculty”. Almost certainly he had clenched his teeth throughout the battle.

The Bohemian folk lullaby repeated by Francis Reeve was recorded by Cormenius. Jan Amos Komenskŷ, or Cormenius, was a protestant Czech scholar and the father of modern education. He recorded the lullaby in his Nursery School Handbook Informatorium Školy mateřské compiled in exile in approximately 1632. The language is archaic Czech. But the first two lines roughly translates as, “Sleep my little bud, sleep my little bird.”

Comenius spent time in England advising on education reform in 1641 at the request of Parliament. He departed in 1642 when the programme was cancelled due to the outbreak of civil war. He declined an offer to be President of the fledgling Harvard University. Instead, he went to work for the Queen of Sweden.

More Reading

I hope you found these historical notes on the battle of Edgehill 1642 useful. You can read more to accompany God’s Vindictive Wrath within the Notes and Maps pages of this website. These include notes on the battles of Aylesbury and Brentford, and the Storming of Winchester in 1642.

You may also wish to read the article about Pike and Shot Warfare. This explains the clash between Dutch and Swedish military doctrines at Edgehill in 1642. This website also includes articles on the General Crisis of the 17th Century and the backdrop of The Thirty Years War. You can also read about the English Revolution and the Great Rebellion of 1642.

Finally, you may wish to check out the posts on Early Modern Life and the British Civil Wars. These include a post on Re-enacting the Battle of Edgehill in 2022. I hope they are of interest.

Alternatively, check out Facebook, Instagram or Twitter for more posts on my historical research, Living History and English Civil War fiction. These include upcoming events and opportunities to meet. You can also follow on social media at #DividedKingdomBooks at:

If you would like more, you might enjoy the Divided Kingdom Readers’ Club. You will receive a monthly email direct from me in which I share more notes from my research. If you think this is for you, please do join the Clubmen.

Spread the Word

If you think others would like what you see, please share via email or your social media:

Alternatively, return to the site Home Page for information about Charles Cordell, latest posts and links to books.